Historic Takoma

History Lives Here

History Lives Here

Stories from Takoma Park’s African American Community

Historic Takoma’s archival collections – city records, maps, personal papers, and photographs — are in many ways the centerpiece for our mission to preserve the history and stories of our city so that residents and scholars can come to know Takoma Park from its founding as an early streetcar suburb in the late 19th century to the vibrant multicultural town it is today. But as is the case for the collections of so many local historical organizations, the stories and people that emerge from these documents skew heavily white.

In 2019 Historic Takoma launched an initiative aimed at collecting the stories of African American families who settled in Takoma Park beginning in the 1920s and ‘30s through subsequent decades, forging their own cohesive community in the midst of racial and economic discrimination. The team that came together for this effort — which includes an oral historian, a documentary filmmaker, and community members with their own knowledge and skills — has focused on conducting oral histories with older residents (current and former) who grew up in Takoma Park.

Like most African Americans in Takoma Park at the time, most of these individuals interviewed lived in one of two neighborhoods (“the Hill,” up on Ritchie, Geneva, Oswego Avenues or “the Bottom,” on Cherry and Colby Avenues off Sligo Creek Parkway). There were also a few homes at the bottom of Lincoln Ave., where the Essex House sits today. They describe how they and/or their siblings attended segregated schools prior to the Supreme Court decision in 1954 – the Takoma School on Geneva Ave. for elementary grades, and then the long bus ride to Rockville for junior high and high school. They share their experiences transitioning to white schools with the advent of integration. They remember the “colored playground,” critical because Black children could not use Montgomery County school playgrounds, and how their parents sought to protect them from racist encounters. The interviews, together with additional research, reflect how African Americans worked to build a resilient community in the face of obstacles and challenges. There’s an obvious sense of urgency to gather these histories while we still have individuals among us who lived through the era of official segregation and the decades that followed.

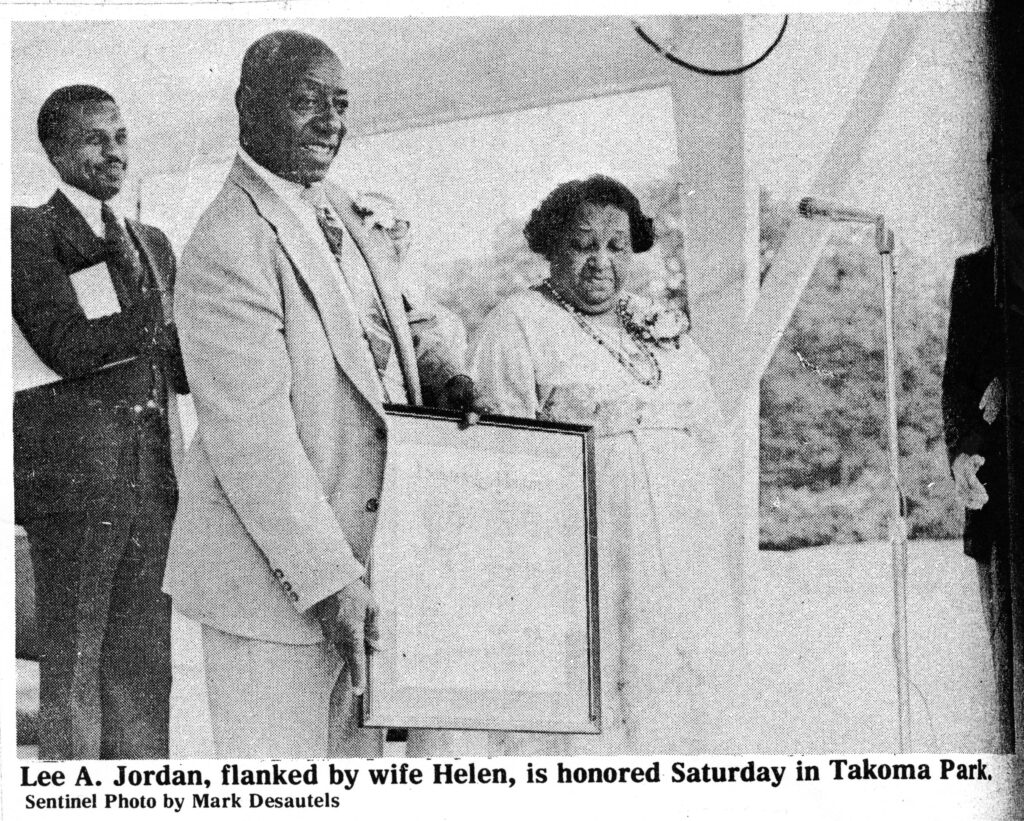

Individuals interviewed to date have been generous with their time, their memories, their insights. The 10-minute film on the legendary Lee Jordan that opened our very successful program for Black History Month in 2020 provides a sampling of these conversations. (See the film, along with the entire program, including comments and testimonials from audience members, on YouTube: Mr. Lee: the Life & Legacy of Lee Jordan.)

The Stories from the African American Community team is working to develop and produce several short videos drawing from the oral histories and additional research, and focusing on various topics and themes. These will be accessible online for use in schools, home viewing, and screenings across the city. We will also plan to produce a book featuring the edited oral history narratives. And the full videotaped oral histories will be available through Historic Takoma’s archives.

This work has been made possible by funding from Takoma Park’s Community Grants Program, with additional support from the Maryland Humanities Council.

Today, of course, our city is home to diverse populations with a wide array of stories, cultural traditions, and challenges. One goal for elevating the voices and stories from Takoma Park’s traditional Black community — and sharing them with audiences across the city — is to provide a touchstone for other initiatives so that, together, we can create a tapestry that deepens our collective understanding of the life experiences of the people who make up our city.